History

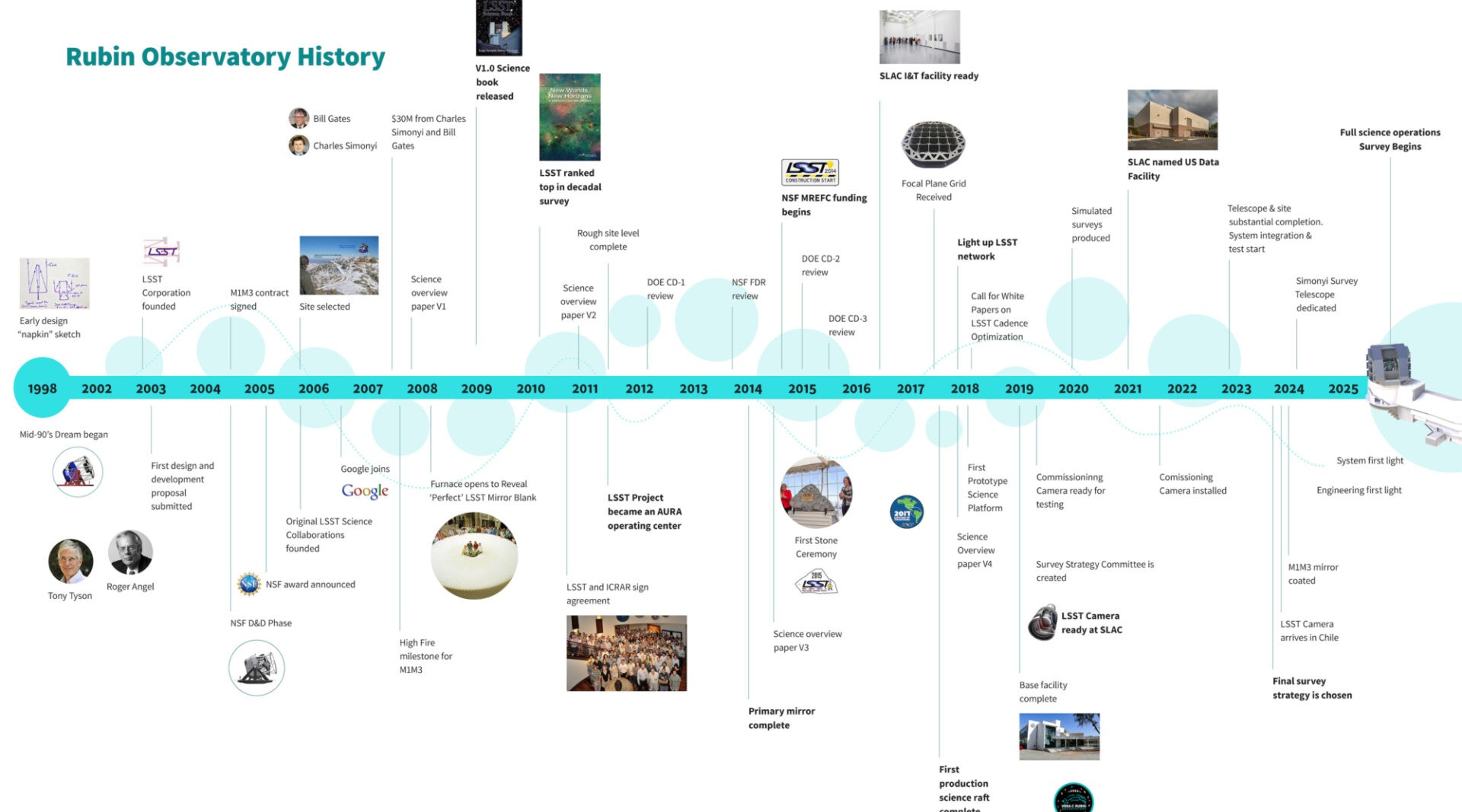

Sometimes great ideas start as sketches on a napkin, and Rubin Observatory is one of those ideas. In the early 1990s, a group of scientists started to plan a new telescope that would push astronomy and astrophysics further than any other telescope built so far. In early brainstorming conversations, they focused mainly on dark matter—what could we learn about this mysterious unseen matter with a telescope that could see more than any other telescope in history? The concept of this “Dark Matter Telescope” evolved over the next few years and gained momentum when a 2001 report by the Astronomy and Astrophysics Survey Committee—"Astronomy and Astrophysics in the New Millennium"—recommended it as a major initiative. By then, this telescope had come to be called the “Large-Aperture Synoptic Survey Telescope,” and scientists were excited about its potential to answer all kinds of science questions, in addition to questions about dark matter.

This new telescope would be able to detect very faint objects. It would catalog 90 percent of near-Earth asteroids—which would help assess the threat of an impact with Earth. The telescope would also be able to image fainter and/or more distant objects in our Solar System than we've ever seen before, which could help us understand more about how the Solar System formed. And it would be uniquely able to detect temporary events, like supernovae, that are easy to miss unless scientists happen to look in the right place at the right time. Most excitingly, data from this telescope would be widely available to both scientists and the public, so more people than ever before could explore the Universe and make discoveries!

Becoming a reality

In 2003, the LSST Corporation was created as a non-profit corporation to support the project. Design and development activity was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), funding from private foundations, individual donors, and member contributions, grants to universities, and in-kind support from US Department of Energy (DOE) laboratories and Member Institutions. The project received a critical boost in 2007 from the software billionaires Charles Simonyi and Bill Gates, who pledged $20 million and $10 million, respectively, to develop the telescope’s mirrors. At that point the project started to feel "real."

Momentum continued to grow after the telescope was prioritized in the 2010 Decadal Survey, an official report released every ten years that recommends the next decade's priorities in astronomy and astrophysics. The project, now called the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), soon received federal funding from NSF and the DOE, and then it was full-steam ahead.

Construction begins

In 2015 a traditional stone-laying ceremony was held on Cerro Pachón, in Chile, to commemorate the official start of construction. All kinds of people who were excited about this telescope attended the event, including the President of Chile! In the same year, at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California, construction officially started on the 3200 megapixel camera at the heart of the telescope.

Over the next few years, construction on different parts of the observatory system continued in different locations around the world—the camera in California, the steel telescope mount structure in Spain, the secondary mirror in New York, and the observatory facility on the summit of Cerro Pachón in Chile. In 2018 everything started to come together—both mirrors and the telescope mount arrived in Chile and were transported to the summit.

A new name

At this point the project was still called the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, but in December 2019, an act of US Congress confirmed our new name: Vera C. Rubin Observatory. This name honors an accomplished American astronomer and acknowledges the contributions to astronomy and astrophysics made by women. Rubin Observatory was the first major, publicly-funded astronomy facility in the United States to be named after a woman.