Camera

Highlights

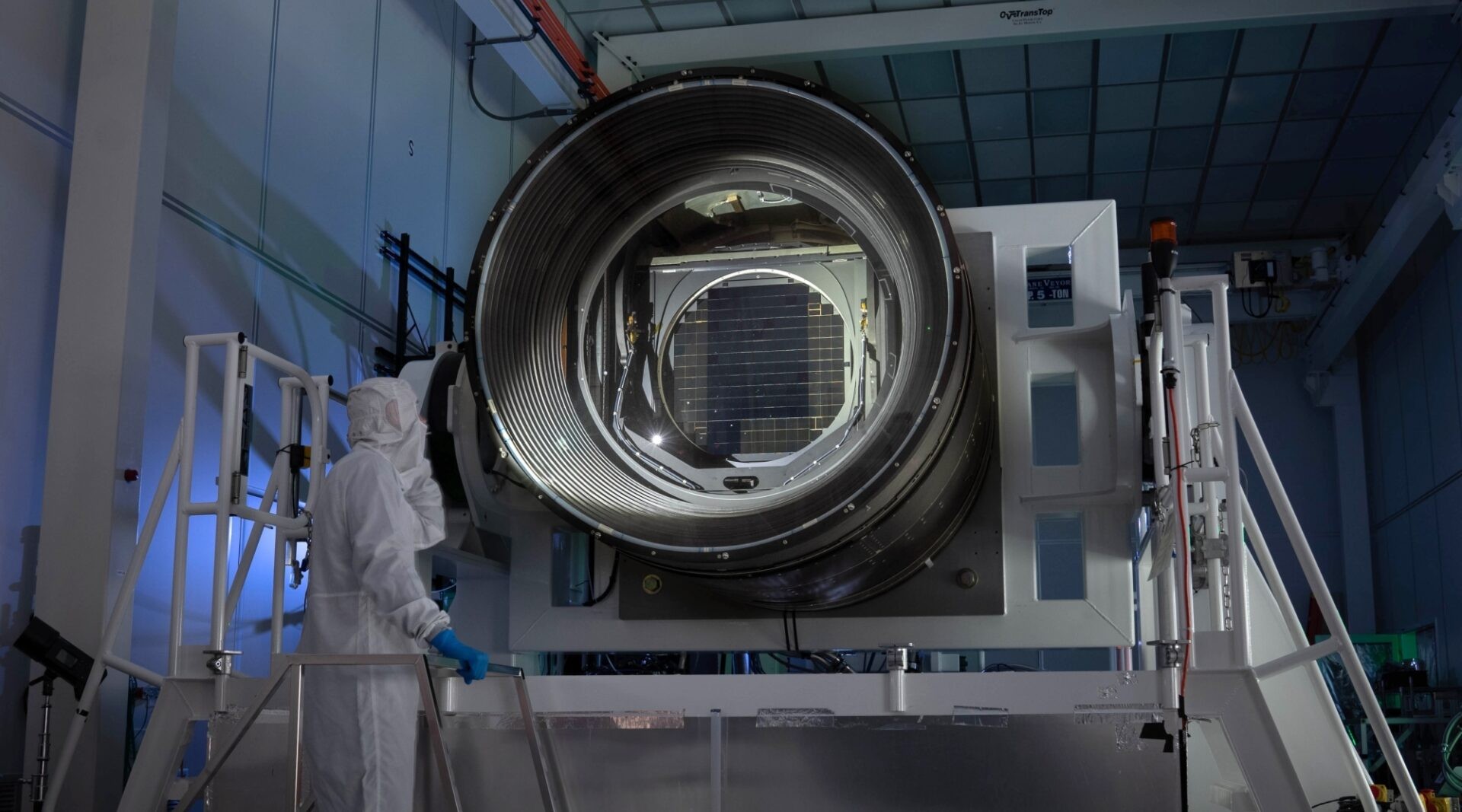

- The camera weighs about 3000 kg (6600 lbs). It’s roughly the size of a small car, but about twice as heavy.

- It would take hundreds of ultra-high-definition TV screens to display a single image taken by this camera.

- The camera’s sensors need to be kept extremely cold (about -100°C or -148°F) in order to limit the number of defective (bright) pixels in images.

- The filters on the camera can be swapped in less than two minutes.

Rubin Observatory's LSST Camera is an impressive piece of equipment. The size of a small car, it's the largest digital camera ever built. Its sensor has a mind-boggling 3200 megapixels—roughly the same number of pixels as 260 modern cell phone sensors. While we certainly won't be taking selfies with the Rubin Observatory camera, we will use it to capture images of billions of far-away galaxies, as well as closer, faint objects that don't give off or reflect much light.

To produce an image of the night sky, Rubin Observatory's large mirrors first collect the light arriving from the cosmos. After bouncing through the mirrors, the light then gets focused by the camera's three lenses onto the image sensors. The camera's electronics convert the light into data, which is then transferred off the mountain and sent to different locations around the world to be processed and readied for science.

This complex and amazing camera was constructed at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California, and it shipped to Chile in May 2024. It will be installed on the Simonyi Survey Telescope in early 2025.

Seeing the Universe in color

Color conveys a wide range of information. Yellow or orange tree leaves on a tree suggest that autumn has arrived, while green leaves suggest spring or summer. Green grass and plants imply plentiful water while brown plants may imply a lack of water. In a similar way, scientists use color in the cosmos to learn more or different information about the objects they study.

The image sensors in telescope cameras or in phones work by measuring the amount of light that hits each location (or pixel) and producing a greyscale image. Without any color filters, the image is brighter where more total light reached the sensor and darker where less total light reached the sensor, regardless of color. So with a red filter, for example, all colors except red light would be filtered out, and the resulting greyscale image would be brighter where there was more red light and darker where there was less red light.

When taking an image of the sky, the Rubin Observatory camera uses one of six different colored filters, labeled with the letters u, g, r, i, z, and y. Each filter lets through a range of colors—from the ultraviolet outside our range of vision (u), through our visible colors (g, r, i), and all the way outside our range of vision in the other direction into the infrared (i, z, y). In other words, telescope cameras have superhuman vision!

The filters themselves are pieces of glass that sit in front of the camera lenses, and they are housed in a carousel so they can be easily switched during observations. Each filter has its own special coating that lets its designated colors of light through while reflecting the other colors. Photographers with handheld cameras can easily attach different filters over their lenses manually, but the Rubin Observatory camera's filters are way too big (each one is 30 in/75 cm across) so we need a sophisticated machine to swap out the filters. This machine, called the auto-changer, can change the filters in less than two minutes.

Rubin Observatory's science goals require the six u, g, r, i, z, and y filters, but the filter carousel isn't able to hold all six filters at once—it's geometrically impossible! That means that on any given night, only five of the six filters can be used. The sixth filter is housed in a special storage stand, separate from the camera, and a device called the filter loader is used to exchange that filter, when it's needed, with one in the carousel (the goal is to limit handling of the filters by hand whenever possible, to reduce the risk of damage). The filter carousel and the filter loader make it easy to change the filter in front of the camera lens often, and that's important because collecting multiple images in all six filters, over 10 years, will provide scientists with a massive amount of information about the entire Southern Hemisphere sky.

Header image credit: Olivier Bonin/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory